It wasn’t until her mother died that she felt the importance of having recipes for the comfort food that she was so used to – dishes she had taken for granted.

Unfortunately, she had not written down or learned any of her family recipes.

“Around the same time, my nephew was born and I realised that he would never get to taste the same food that me and my brother had grown up eating,” she says.

How ex-Chaat chef’s Indian dishes ‘sing the songs of olden times’

How ex-Chaat chef’s Indian dishes ‘sing the songs of olden times’

“Home food is so accessible and taken for granted that we sometimes don’t realise how valuable it is.

“Home food is part of your culture and identity and family recipes are tangible heirlooms, as valuable as jewellery or saris that people want to preserve.”

One dish that anchored her was the kala chana (black chickpeas) made by her mother for Sunday lunches, where any leftovers would be combined with boiled potatoes and repurposed as a tasty paratha (flatbread) the next day.

The chana was made in a special iron kadai (wok) that would add to the black colour of the dish.

“I also like my rajma [kidney beans in gravy] a particular way – in a thick gravy with pudhina [mint] chutney and broken roti dipped in it,” says Taneja.

“Food that our mothers and grandmothers cooked was an expression of their love for their family, and they would always be mindful of individual tastes and remember things like the fact that I loved my gravy thick and not watery.”

Singaporean chef on her pan-Asian plant-based cookbook

Singaporean chef on her pan-Asian plant-based cookbook

Another family dish was a special lentil kachori (a deep-fried snack) that her grandmother would make every birthday; she had brought the recipe from Pakistan when she migrated to India.

Taneja launched Nivaala in 2021 as a platform that helps families document their family recipes. “It started off as a passion project but now has snowballed and grown organically into something much larger,” she says.

She started off by just selling blank journals in which users could record the generation that created the dish, associated memories, ingredients and the recipes themselves.

A rich culinary heritage may disappear, so record these family recipes before it’s too late

She later began another project, Andaaz Publishing, in partnership with Chinmayee Manjunath, an editor and communications strategist, that helps families gather and publish their recipes in a well-designed cookbook.

This is akin to a safe locker that future generations can access, to understand their family food culture.

Families send them the recipes, the backstory, ingredients lists and photographs of the dish, which are then compiled into a book.

“These books make great gifting options on special occasions such as weddings or birthdays. They also help to rekindle and keep nostalgia for the past alive in a family, and pass on recipes that would otherwise be lost,” says Taneja.

“We have had many men who come to us with recipes, wanting the book to be published as a gift for their mums or sisters.”

Taneja also collaborates with chefs across India. In one project she worked with a farm, chose an ingredient produced by it, and asked famous chefs to send recipes that had incorporated the hero ingredient.

Why aren’t cookbooks dead yet? ‘It isn’t only about the cooking,’ chef says

Why aren’t cookbooks dead yet? ‘It isn’t only about the cooking,’ chef says

The ingredients she has chosen include mushroom, jackfruit and rajma. And the recipes, anecdotes and memories she collects are compiled to showcase the incredible diversity of Indian cuisine, and how versatile one ingredient can be.

Rajasthan Micro Cuisine Project is another upcoming collaboration that Taneja is working on with The Kindness Meal, a Jaipur-based dining community; together, they aim to rediscover micro cuisines and cooking methods from across India’s largest state.

Taneja recently took a road trip across one region in the western desert state, travelling to small towns and villages, collecting family recipes. “Just in that region we collected over 90 recipes – imagine the diversity across India,” she says.

She will soon post these recipes online so that people can refer to them.

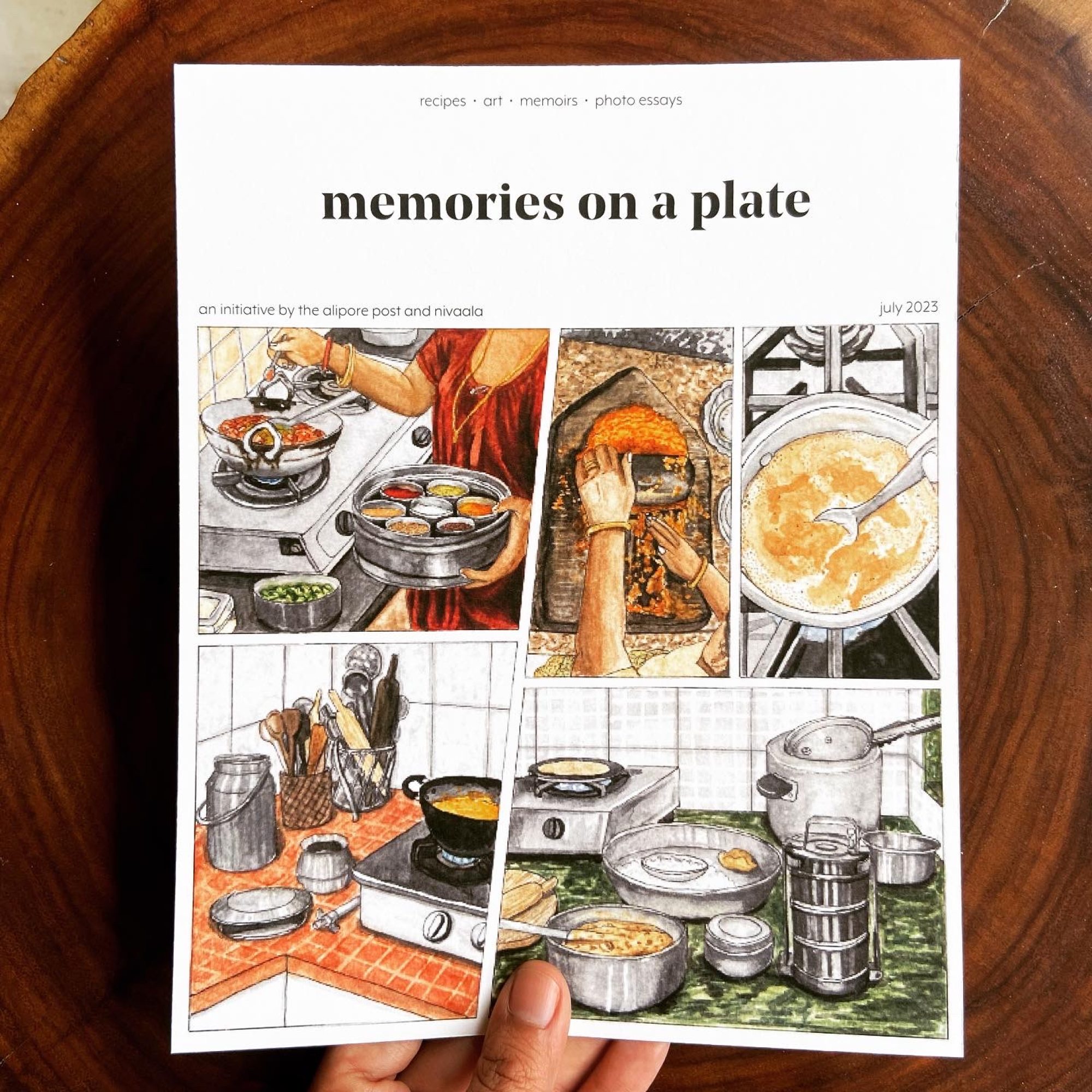

Another coming project that she has been involved in, called Memories on a Plate, is a collaboration with Rohini Kejriwal, founder of culture newsletter The Alipore Post.

“It is an anthology of 100 recipes from Indian kitchens across the world, with anecdotes, recipes, artwork, photo essays and poetry with QR codes linked to food memories and recipes,” says Taneja.

They received more than 350 submissions from chefs, home cooks and culinary students across the globe, out of which 100 were selected. “It was a heartwarming experience to put together all these memories associated with food,” says Taneja.

For this project, they are collaborating with the Mumbai-based non-profit Khaana Chahiye Foundation to donate one meal from each book sale.

“One thing that Covid-19 has taught all of us is that mortality is real, and we are not going to be here forever,” she says.

“People will go away and with them a rich culinary heritage may disappear, so record these family recipes before it’s too late.”

Article From & Read More ( The Indian cookbooks preserving ‘a legacy’ by recording old family recipes - Post Magazine )https://ift.tt/G98oLdR

Entertainment

No comments:

Post a Comment