Modern cake recipes instruct the cook to set the oven to 200C or to plug in the electric mixer. But what if they told you to heat the wood stove or to mix the batter with only a wooden spoon?

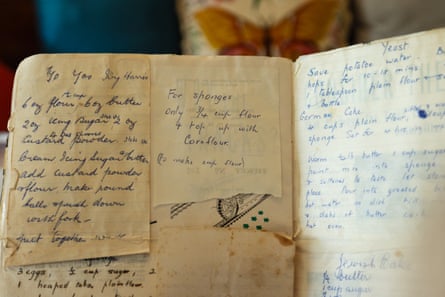

Author Liz Harfull sifted through hundreds of Australian community cookbooks from the last 100 years, converting the recipes for the modern day for her 2018 cookbook Tried, Tested and True. It was a task that involved “quite a bit of detective work”, she says.

“If you go back to the mid 1800s … the recipes are written almost like a story,” Harfull says.

“Then you get up to the early 1900s and they’ve been stripped right back … and they’ve got practically no method at all. They assume a really high level of knowledge.”

Some differences are particularly stark. Ovens had no temperature gauges and recipes only asked for them to be set to “hot” or “moderate”. Measurements were similarly vague.

“A lot of the older recipes talk about cups, and the cup could be one of about four different sizes,” says Harfull. “There was a coffee cup and there was the teacup. And there was a breakfast cup.”

Today, we take specificity for granted: preparation times are counted to the minute, cooking steps contain detailed instructions and describe the colours and textures of the batter at each stage.

Cookbooks from the turn of last century were lean on detail because they relied on the assumed knowledge of the reader, who typically would cook and learn alongside someone from an older generation. It wasn’t until the 1950s and 60s that recipes became more detailed, says Harfull, as women entered the workforce in greater numbers and spent less time cooking in the home.

Kaitlyn Sawrey is fascinated by the ways we used to bake. “Recipe books tell a bigger story about our world and the place we live in, just based on necessity and what’s practical, but also what’s trendy,” she says. Along with co-producer Frank Lopez, Sawrey hosts a podcast called Cake, which explores the culinary history of Australia’s baked goods.

Take lamingtons – the subject of the first episode of the series. The chocolate-and-coconut cake cubes were prized for their transportability. “They keep quite well, because you’ve got the chocolate sauce, keeping the inside moist, and because it’s rolled in coconut it’s not melting everywhere,” says Sawrey.

The cake’s popularity reached new heights in the 1950s when the Australian Women’s Weekly published a lamington recipe and the cakes soon featured at lamington fundraising drives, Girl Guide and Boy Scout events and on election days.

Sweet recipes including lamingtons, sponge cake and scones have largely stood the test of time. “What was a good cake 100 years ago is pretty much still a good cake,” Harfull says.

But not every cake enjoys that fate. The national appetite for fruitcake, in particular, has waned Sawrey says.

“Fruitcake was something that was really popular … It’s the sort of thing that keeps for a really long time, you don’t need to refrigerate it, there was a huge dried fruit industry in Australia.”

Rise of refrigerators aside, Gloria Buck believes a change in accessible ingredients has contributed to the fruitcake’s lost lustre. Twenty years ago, after avoiding the kitchen for most of her life, she came across a box of recipes that belonged to her late aunt, an award-winning show cook. Among these recipes was her signature fruitcake.

Since finding the recipe, Buck has baked many fruitcakes and won several competitions herself. She says in the two decades since her first fruitcake, the quality of dried fruit has diminished and the all-important brandy is more expensive. For the best fruitcake, you need the freshest eggs – and Buck says with supermarket eggs that can be difficult to know.

Brandy aside, Harfull says most classic recipes are actually fairly frugal. “I find it fascinating how many extraordinarily different variations the older cooks could make from just the basic ingredients – butter, eggs, flour, sugar and milk,” she says.

“The permutations of what you can create, from scones to biscuits to slices to cakes to puddings is quite extraordinary … just by changing the technique and the ratio.”

Buck too admires her forebears’ dedication. “I remember seeing my grandmother sit with her feet by the oven, hand-mixing cakes for hours on end,” she says. That being said, Buck is grateful technology has made her own efforts easier. “Now it’s a lot quicker and a lot less stress.

“They never had electric mixers … that does make life much easier, just to put the Kenwood on.”

Article From & Read More ( Great vintage bake-off: why lamingtons survive while fruitcakes fell from favour - The Guardian )https://ift.tt/3pasgeP

Entertainment

No comments:

Post a Comment